Intro to Soft Systems Methodology

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) provides a philosophy and a set of techniques – a method – for investigating a “real-world” problem situation. SSM provides an approach to participatory design that focuses on human-centered information systems by analyzing organizations as systems of human-activity. It also provides an excellent method for surfacing multiple perspectives in decision-making, complex problem-analysis, and socially-situated research. The analysis tools suggested by the method — which is really a family of methods, rather than a single method in the sense of modeling techniques — permit change-analysts, consultants and researchers to explore alternatives for change, while exercising reflexivity in considering the effect of their own prejudices and biases on the analysis.

SSM could be described as an approach to change requirements analysis, rather than a systems design or IT requirements approach. It questions what operations the system-of-work should perform and, more importantly, why. The approach provides a “soft” investigation (into what the system should do) which can be used to precede the “hard” investigation (into how the system should do it). The approach focuses on the investigation of situated problems that may or may not require computer-based system support as part of their solution. It investigates an unstructured problem situation that is viewed as a governed by business logic, rather than the engineering logic normally attached to IT system requirements. Unlike most systems requirements analysis techniques (e.g. UML, entity-relationship modeling or data-flow diagrams), which focus on how the computer system should operate, SSM focuses on the system of work – the “human activity system” that requires computer system support. SSM asks the fundamental question that should (but usually does not) precede system requirements analysis:

“Why do we want a computer system and what role will it perform, in supporting people and organizational work?”

The analysis is based upon a simple concept: that we model systems of purposeful human activity (what people do), separating these out into sub-systems that serve different purposes in order to understand the complexity involved. It models the sequence and interactions of human processes rather than data-management or IT components (the more usual focus of systems analysis). It is systemic, rather than systems-focused, calling upon the tradition of general systems theory (von Bertanlaffy, 1968) and inquiring systems (Churchman, 1971) in acknowledging the disparate elements of a situation. SSM is helpful for analysis approaches that wish to understand the connections, conflicts, and discrepancies between elements of a situation rather than attempting to subsume all elements into a single perspective.

The Origins of SSM

Soft Systems Analysis is based on Vickers’ concept of Appreciative Systems (Vickers, 1968; Checkland, 2000b). Geoffrey Vickers observed the diversity of norms, relationships, and experiential perspectives among those involved in, or affected by, a system of human-activity such as that found in business work-organizations. He argued that organizational change analysts needed methods for analysis that explored how to reconcile these perspectives, developing the concept of an “appreciative system,” the set of iterative interactions by which we explore, interpret, and mutually construct our shared organizational reality (Vickers, 1968), shown in Figure 1.

(Source: Checkland and Casar (1986), via Checkland (2000b)

Vickers conceptualized organizational work as a stream, or flux, or events and ideas that were interpreted by participants in the organization by means of local “standards,” reflecting shared interpretation schema and sociocultural values (Checkland and Casar, 1986). Interpretations of new events and ideas are subject to the experiential learning that resulted from prior encounters with similar phenomena; these will vary across stakeholders, depending on how they interpret the purpose of the system of work-activity. To achieve substantive change, we need to understand and reconcile these multiple purposes, integrating requirements for change across the multiple system perspectives espoused by various stakeholders. These are separated out into distinct perspectives, which model subsets of activity that are related to a specific purpose or group of participants in the problem situation (Checkland, 1979, 2000b).

From Appreciative Systems To Soft Systems

Following from his studies of the appreciative systems approach to change and IT requirements analysis, Checkland (1979) focused on the analysis of SOFT SYSTEMS, purposeful systems of human activity that represent how various business processes, groups, or functions work, are organized,and interact. The idea is to apply systems theory to the modeling of organizational work, representing what people do (or need to do, to achieve their goals) rather than losing sight of stakeholder perspectives as we model information or technology architectures.

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) provides a framework for the analysis of organizational change. It focuses on the human activities required to achieve participant-goals, using a divide-and-conquer approach to manage complexity. The method starts by exploring unstructured representations of the problem-situation in context, then models relevant “systems of human-activity” that achieve purposes valued by participants. Each human-activity system is compared to work activities in the real world, to identify areas where changes could improve outcomes, improve coordination, or otherwise improve organizational work as a whole. The set of changes is prioritized and implemented, then evaluated – after a suitable time-lag – to determine the effects of change and identify aspects of organizational work that might be explored in the next iteration. This process is shown in Figure 1.

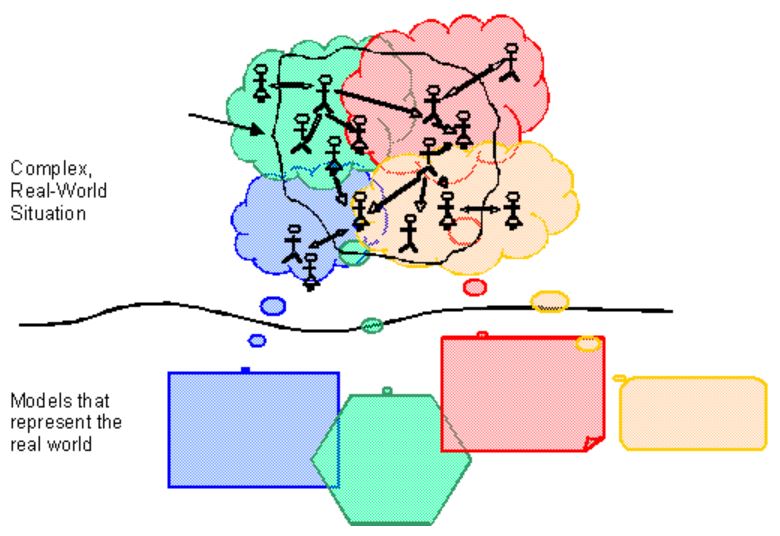

SSM provides a way of engaging in joint learning with stakeholders and participants about the problem-situation. It allows all parties involved to understand the implications of achieving various purposes and involves participants in defining relevant work-activities and exploring what needs to change. Initially, the process of inquiry focuses on the real-world problem-situation, exploring how this works using representations such as Rich Pictures, which impose as little structure on what exists as possible. In this way, we get to appreciate how this world “works” rather than viewing it through the filter of the models we construct. Whatever insights a model may give us, it does not represent the real world. Instead, it represents systems thinking about the real world. Checkland (1979) distinguishes between “above-the-line thinking” (about entities, relationships, and activities performed in the real-world situation) and “below-the-line thinking” (which models the potential/ideal-world sub-systems of human-activity required to achieve each separate purpose of the real-world system). Below-the-line thinking produces the “Relevant models of purposeful activity” shown in Figure 2, above. These are separated out, as shown in Figure 3, so we can model and analyze the activities required to achieve each purpose separately.

The SSM Analysis Process

The point of all this modeling is to provide ongoing cycles of organizational learning. Employing a systemic analysis means that we involve managers and participants in one functional area in modeling and analyzing the enterprise-wide business processes of which their work is a part. Each person gains a view of what others do in the organization, and an interior perspective of others’ problems and priorities. People start thinking in terms of organizational values and interests, rather than their own fiefdoms. The conventional seven-stage model of SSM is shown in Figure 2. A major criticism of this model — later made by Peter Checkland himself — is that it is too linear to represent the actual process of inquiry that SSM requires. Whilst most SSM analysts would accept that, this model provides a useful starting point for novice analysts.

The stages of SSM modeling are described in the following pages. The idea is to represent the problem-situation in ways that make sense to those involved in working there. The method allows us to separate real-world thinking – representing the various purposes that participants ascribe to their work, what they do to achieve these, and what problems they experience – from systems thinking about the real world – tracing how these purposeful systems of work interact, complementing or conflicting with each other, exploring how outcomes are evaluated and which outcomes are not evaluated, and investigating why/how problems occur in the wider scheme of roles, responsibilities, purposes, and coordination mechanisms.

In the pages that follow, I have included some examples of how to produce and use SSM models and processes, to explain the value of exploring problems systemically.

SSM is based upon the idea that we model systems of purposeful human activity (what people do), rather than data-management or IT components (the more usual focus of systems analysis). It is systemic, rather than systems-focused, calling upon the tradition of general systems theory (von Bertanlaffy, 1968) and inquiring systems (Churchman, 1971) in acknowledging the disparate elements of a situation. SSM is helpful for analysis approaches that wish to understand the connections, conflicts, and discrepancies between elements of a situation rather than attempting to subsume all elements into a single perspective.

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) was devised by Peter Checkland and elaborated in collaboration with Sue Holwell and Jim Scholes (among others) at Lancaster University in the UK. SSM provides a philosophy and a set of techniques for investigating a “real-world” problem situation. SSM is an approach to the investigation of the problems that may or may not require computer-based system support as part of its solution. In this sense, SSM could be described as an approach to early system requirements analysis, rather than a systems design approach. This website attempts to explain some of the elements of SSM for educational purposes. It is not intended as a comprehensive source of information about SSM and may well subvert some of Checkland’s original intentions, in an attempt to make the subject accessible to students and other lifelong learners … ![]() .

.

References

Checkland, P. (1999) Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: includes a 30-year retrospective. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. ISBN: 0-471-98606-2.

Checkland, P. & Scholes, J. (1999) Soft Systems Methodology in Action. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. ISBN: 0-471-98605-4.

Checkland, P., Holwell, S.E. (1997) Information, Systems and Information Systems. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Chichester UK. ISBN: 0-471-95820-4.

Checkland, P., Poulter, J. (2006) Learning for Action: A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology and its Use, for Practitioners,

Churchman, C.W. (1971) The Design of Inquiring Systems, Basic Concepts of Systems and Organizations, Basic Books, New York.

von Bertanlaffy, L. (1968) General System theory: Foundations, Development, Applications, New York: George Braziller, revised edition 1976.